How to Mentor Instead of Manage

Reclaiming Influence, Connection, and the Joy of Learning at Home

At some point—often quietly, sometimes suddenly—many parents realize that much of their energy is going into managing.

Managing schedules.

Managing assignments.

Managing attitudes and expectations.

It starts with good intentions. A desire to help. A fear of falling behind. And slowly, leadership gives way to control.

Most families didn’t choose an alternative path for this. They wanted connection. A love of learning. A home marked by trust instead of tension.

But when management takes over, something essential is lost. Learning becomes about compliance. Responsibility shifts outward. And the relationship begins to strain.

Here’s the hopeful truth: mentoring isn’t a method—it’s a posture.

A choice to lead through influence rather than control.

To model growth instead of enforcing outcomes.

To trust that education is something a child eventually claims, not something a parent successfully manages.

And that shift changes everything.

Management vs. Mentoring: A Different Way to Lead

Management and mentoring may look similar on the surface, but they are driven by very different assumptions about learning, leadership, and human growth.

Management focuses on outcomes.

Did the work get done?

Was the requirement met?

Did we stay on schedule, finish the lesson, check the box?

But children are not systems to be optimized.

Mentoring focuses on growth.

Who is this child becoming?

What habits of mind are taking root?

What kind of adult is being formed beneath today’s assignments?

Where management seeks immediate compliance; mentoring cultivates long-term ownership.

This distinction matters because no one becomes a self-directed adult by being managed well.

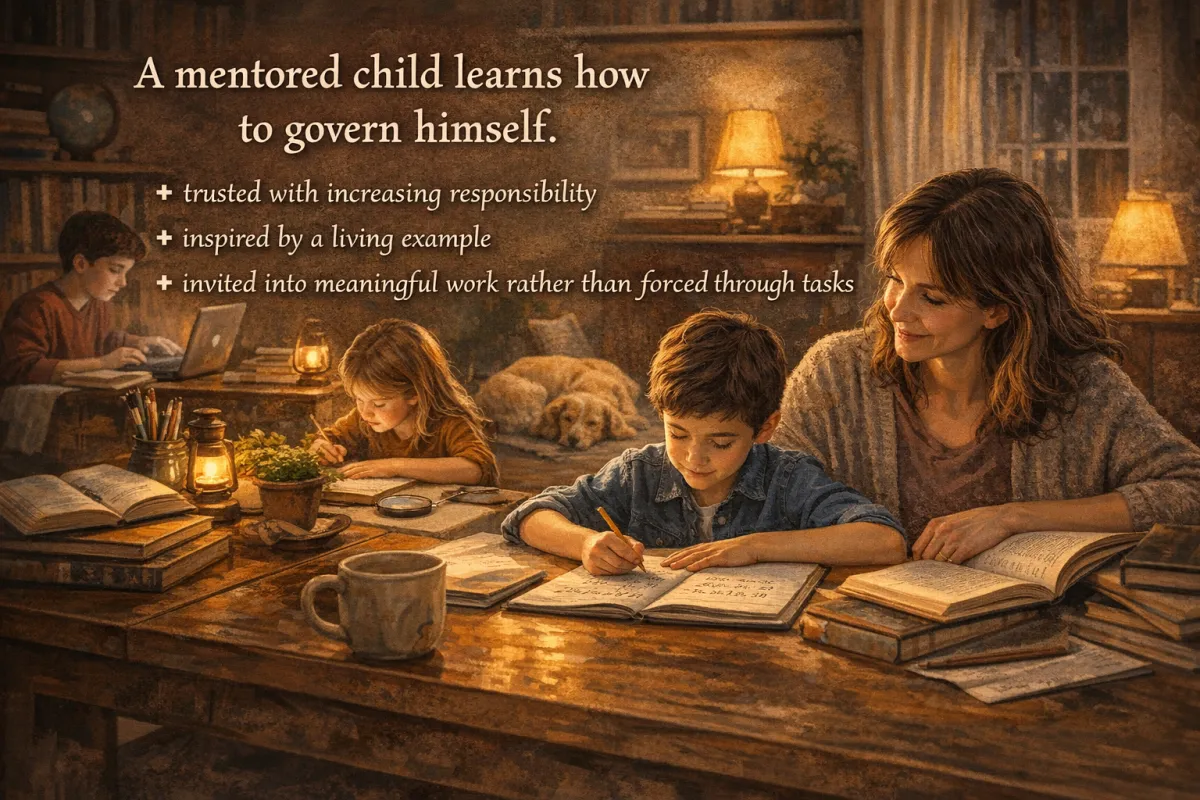

Self-direction grows when a young person is:

trusted with increasing responsibility

inspired by a living example

invited into meaningful work rather than forced through tasks

A managed child learns how to respond to external authority. A mentored child learns how to govern himself.

Management asks, “How do I get this done?”

Mentoring asks, “How do I help this child grow into someone who chooses to do what matters?”

One produces short-term order.

The other produces long-term capacity.

This is why families often feel an internal conflict. Management “works”—until it doesn’t. It can produce tidy days, completed checklists, and outward progress, while quietly undermining the very traits parents hope to cultivate: initiative, curiosity, resilience, and personal responsibility.

Mentoring, on the other hand, often looks slower at first. It requires patience. It asks the parent to resist urgency driven by fear. But over time, it produces something far more powerful than compliance: ownership.

When children are mentored rather than managed, learning stops being something done to them and becomes something they begin to claim for themselves.

And that is the goal—not obedient students, but capable, thoughtful, self-governing adults.

Mentoring Begins With You

One of the most freeing—and sometimes unsettling—truths in Leadership Education is this:

Education doesn’t begin with the child. It begins with the parent.

Not with your plans.

Not with your curriculum.

Not with your expectations.

It begins with who you are becoming.

Children learn who we are long before they absorb what we say. They are exquisitely attuned to our posture toward life. They notice whether we approach challenges with curiosity or avoidance, whether we keep commitments or quietly excuse ourselves from them, whether learning feels alive in us—or merely obligatory.

This is why mentoring cannot be outsourced to a checklist.

A mentor is not primarily someone who assigns work. A mentor is someone who models a way of living. And in the home, that role is unavoidable. Even when we try to step back, we are still teaching—through tone, habits, priorities, and example.

The good news is that you do not need to be a teaching expert to be an effective mentor.

You don’t need to know more than your child.

You don’t need to have everything figured out.

You don’t need to be further down the path than you feel ready for.

You need only to be willing.

Willing to learn.

Willing to grow.

Willing to let your children see you reading, wrestling with ideas, asking questions, and stretching beyond what is comfortable.

This is why mentoring is so different from managing. Learning stops looking like a task imposed by authority and starts looking like a meaningful part of adult life.

Management says, “Do this because I said so.”

Mentoring says, “Come with me. This matters.”

When parents shift their focus from controlling outcomes to cultivating their own growth, pressure begins to lift from the relationship. The home becomes less about enforcement and more about invitation.

And paradoxically, as parents release control in the right ways, their influence increases.

Because children are far more likely to follow a living example than a set of instructions.

Mentoring begins the moment a parent decides that their own education—their habits, character, and curiosity—is not a distraction from their child’s learning, but the foundation of it.

Freedom Requires Form

Mentoring does not mean the absence of rules.

In fact, mentoring only works when it is paired with clear boundaries, real expectations, and a well-ordered home. Freedom without form is not Leadership Education—it’s drift.

In academics, children need increasing freedom. They need space to practice ownership, to choose effort, to wrestle with ideas, to experience the natural consequences of commitment and follow-through. This is where mentoring replaces managing, and where long-term self-government is formed.

But that freedom rests on a foundation of structure.

In matters of executive function—sleep, screens, entertainment, friendships, work habits, and home responsibilities—parents must lead with clarity and firmness. These are not areas for negotiation or experimentation. Children borrow executive function from adults until they develop their own. That borrowing requires limits.

A well-run home has:

clear rules

predictable rhythms

meaningful work

real responsibilities

and consistent follow-through

Jobs in the home matter. Chores are not punishments; they are training in contribution and competence. Discipline is not about control or emotional reaction—it is about order, safety, and learning to live within reality.

Time blocks for academics are part of this order. Freedom does not mean “whenever, however.” It means within a structure that protects what matters. When the day has shape, children are far more capable of using their academic freedom well.

Leadership Education is not permissive. It is intentional.

We are not saying, “Let your children run the house.”

We are saying, “Run the house well—so your children can learn to run themselves.”

Proper rules create peace.

Clear boundaries create safety.

Order creates the conditions where freedom can actually work.

When parents hold the line on structure and responsibility, they earn the credibility to release control where it counts most—in learning, thinking, and becoming.

That balance is not a contradiction.

It is the heart of mentoring.

Practical Mentoring Strategies

Mentoring is not a single tactic. It is a pattern of choices that, over time, reshape the culture of learning in your home. The following practices are simple, but they are not shallow. Each one shifts responsibility from the parent to the child while strengthening the relationship that makes real learning possible.

1. Model the Life of a Learner

One of the most powerful mentoring tools requires no lesson plan at all.

Learn something….for yourself.

Choose a book that stretches you. Revisit a subject you once loved. Learn a skill that has nothing to do with your child’s current studies. Then let your children see you doing the work.

You don’t need to announce it or turn it into a teachable moment. Simply allow learning to be visible. Mention an insight at the dinner table. Share a frustration. Express delight when something clicks.

When children see learning as something adults choose—rather than something children are required to endure—it quietly reframes their expectations. Education stops looking like a phase to outgrow and starts looking like a way of life.

This is mentoring at its most natural.

2. Replace Directives With Curiosity

Management often sounds like instruction: Do this. Finish that. You need to…

Mentoring sounds more like curiosity.

What do you think about that?

What was hard?

What do you think your next step should be?

Questions invite ownership. They signal respect. They communicate that the child is not merely completing tasks, but developing judgment.

This doesn’t mean parents never give direction. It means direction is offered in the context of conversation rather than command. Curiosity slows things down just enough for a child to engage mentally instead of reacting emotionally.

Over time, children begin asking themselves the same questions you once asked them.

That is the quiet transfer of leadership.

3. Read Together to Connect

Few practices shape a mentoring relationship more powerfully than reading aloud.

Reading together creates shared language, shared imagination, and shared reference points. It allows ideas to enter the home without confrontation. It invites discussion without forcing conclusions.

There is no need to quiz or analyze excessively. Let conversation emerge naturally. Sometimes the most meaningful discussions come days later, sparked by a line that lingered.

Read above your children’s level. Read things that move you. Read not to cover material, but to encounter ideas worth wrestling with.

When families read together, mentoring happens almost effortlessly.

4. Stop Managing the Timeline

Much management is driven by fear—fear of falling behind, fear of missing a window, fear that if something isn’t mastered now, it never will be.

Mentoring honors readiness.

This doesn’t mean abandoning standards or expectations. It means recognizing that depth cannot be rushed and that real learning follows internal timing more than external schedules.

When parents loosen their grip on the timeline, children often rise to responsibility more quickly, not less. Pressure lifts. Resistance softens. Ownership becomes possible.

Sometimes the most effective step forward is a strategic step back.

5. Let Effort Matter More Than Performance

Management praises results. Mentoring notices effort.

This shift seems small, but its impact is profound.

When children learn that perseverance, honesty, and follow-through matter more than appearance or perfection, they become willing to try hard things. They take risks. They stay engaged when learning becomes uncomfortable.

Praise effort. Acknowledge persistence. Name growth when you see it.

Performance may fluctuate. Character compounds.

6. Talk About What You’re Learning

Make learning conversational.

Share insights casually. Wonder aloud. Ask questions that don’t require answers. Let curiosity be part of daily life, not something confined to “school hours.”

When learning is woven into normal conversation, it stops feeling like an event and starts feeling like a posture.

And that is the culture mentoring creates.

When It Feels Like You’re Doing It Wrong

There are moments—often many—when parents trying to mentor instead of manage feel deeply uncertain.

The structure is looser.

The outcomes are less immediate.

The feedback is quieter.

And in that quiet, doubt finds space.

Shouldn’t this look more productive?

What if I’m being too hands-off?

What if this works for other families—but not for mine?

These questions aren’t signs of failure. They’re signs that you’ve stopped relying on external validation to measure success. Management offers constant reassurance—boxes checked, schedules followed. Mentoring rarely does.

Instead, it asks you to trust a longer arc.

Mentoring isn’t something you “arrive at.” There are seasons of clarity and seasons of uncertainty, days that feel connected and days that feel like nothing is sticking. This isn’t a problem to fix—it’s part of the work.

Growth is rarely linear. Children test limits. Parents second-guess themselves. Old habits resurface under stress. That doesn’t negate the mentoring posture; it simply reminds us we’re human.

Grace matters here—especially toward yourself.

When things feel messy, return to first principles:

Am I modeling the life I hope my child will choose?

Is our relationship intact?

Am I inviting growth, or forcing outcomes?

If those answers are moving in the right direction, you’re not failing—you’re trusting the process.

Mentoring requires trust: in your child, in the process, and in the quiet work of growth. And often, when you’re not looking for it, you’ll see the evidence—in a thoughtful question, an unprompted effort—and realize something important has been growing all along.

What Mentoring Builds Over Time

Mentoring rarely produces immediate, visible results. Its work is quiet. Incremental. Often unnoticed in the moment.

But over time, its effects are unmistakable.

Where management produces compliance, mentoring produces capacity. Where management holds things together through effort and oversight, mentoring builds something that holds even when you step back.

The first thing mentoring builds is relationship.

When children experience their parent as a guide rather than a supervisor, trust deepens. Conversations become more honest. Resistance softens. Children feel safer admitting confusion, doubt, or even disinterest—because they know the relationship is not contingent on “performance”.

From that foundation, mentoring builds independent thinkers.

Children who are mentored learn how to wrestle with ideas, not just absorb information. They become comfortable asking hard questions, sitting with ambiguity, and forming opinions that are genuinely their own. They are less dependent on external validation and more anchored in internal standards.

They also begin to develop self-governance.

This is one of the most misunderstood outcomes of mentoring. Letting go of control in the right ways does not produce chaos—it produces responsibility, when done with patience and principle. Over time, children begin to manage their own work, their own time, and eventually their own goals, because they have practiced doing so in a safe, relational environment.

Perhaps most importantly, mentoring builds a peaceful learning culture.

When pressure lifts, learning becomes less adversarial. The home no longer feels like a battleground of wills. Curiosity re-emerges. Joy returns—not because everything is easy, but because the work is shared and meaningful.

These outcomes do not arrive all at once. They accumulate slowly, like compound interest. And they often reveal themselves years later, when a young person chooses to take ownership of something difficult—not because they were forced to, but because they have learned how.

That is the fruit of mentoring.

It doesn’t just prepare children to succeed under supervision. It prepares them to thrive when no one is watching.

From Control to Influence

Parents often fear that releasing control will lead to drift. But mentoring does not abandon leadership; it refines it. Influence grows not from tightening the reins, but from earning trust, modeling purpose, and inviting responsibility.

Control requires constant presence. Influence endures—even when you step back.

Children who are mentored do not simply learn how to meet expectations. They learn how to set them.

They begin to ask better questions.

They develop internal standards.

They discover that learning is not something imposed for a season, but something claimed for life.

This is why mentoring matters far beyond academics.

A child who has been mentored learns how to approach a book, a problem, a calling, or a crisis without waiting to be told what to do. They have practiced thinking, choosing, and persisting in the presence of guidance rather than pressure.

And just as importantly, the relationship remains intact.

When parents lead through influence rather than control, the home becomes a place of shared purpose rather than constant negotiation. Respect flows both directions. Authority rests on trust instead of enforcement.

This is not a quick fix. It is a long view.

But over time, mentoring replaces exhaustion with confidence, tension with connection, and fear with clarity. Parents stop asking, “How do I make this work?” and start asking, “Who is my child becoming—and how can I support that growth?”

That shift changes everything.

Because the ultimate goal of education is not that children do what they are told, but that they grow into adults who know how to lead themselves—and, one day, others.